The Nazis were known to keep meticulous records on just about everything. Amazingly, this was also true about their desire to establish a photographic record of their crimes. We are familiar with Hitler’s favorite filmmaker and director, Leni Riefenstahl (1902−2003). She was not only a filmmaker but also a photographer and yes, a Nazi. Her movies included Olympia (1936 Berlin Olympics) and the propaganda film on the 1934 Nazi rally at Nuremberg. There was Heinrich Hoffmann (1885−1957), Hitler’s personal and official Nazi photographer. Hoffmann was part of Hitler’s inner circle and played a significant role in Goebbel’s propaganda program to elevate Hitler in the eyes of German citizens. Both of these individuals are quite well known due to their historical visibility. However, there was a group of photographers who are not quite as famous as the Nazi propagandists. These were the Auschwitz photographers and they were inmates selected by the camp’s commandant, SS-Hauptsturmführer Rudolf Höss.

Did You Know?

Did you know there was a man whose hobby was collecting artifacts from flea markets, estate sales, and other venues? Sounds kind of normal, right? Well, what is different is that the items he collected had names on them. His real hobby was the journey he took to return the items to their original owners.

Barbara Sieder Treadway recently received a letter from an attorney in San Diego. He asked Barbara if she was related to Russell Sieder, a soldier killed during the Korean conflict. The last time she saw her brother was on Christmas just before he shipped out to Korea. He was killed in March 1953 leading a charge up a hill. Russell is buried in Arlington next to his father who helped plan the invasion of Normandy on 6 June 1944.

The attorney explained that his father had this unique hobby of collecting stuff with peoples’ names displayed and the goal was to return the items to the person named on the artifact. The attorney had a handmade box with Lt. Russell Sieder’s name and serial number written on it. After Barbara confirmed she was Russell’s sister, the attorney sent her the box. The box remains a mystery, but it now occupies a very visible place in Barbara’s home. It is a reminder of the happy days she spent with Russell when brother and sister were young.

Thank you to John Hackworth, commentary editor of the Charlotte Sun Newspaper, for writing about Barbara and Russell. It’s a nice story intermingled with a lot of not-so-nice news. A nice Christmas present for Barbara.

Happy holidays everyone.

Stew and Sandy

Wilhelm Brasse

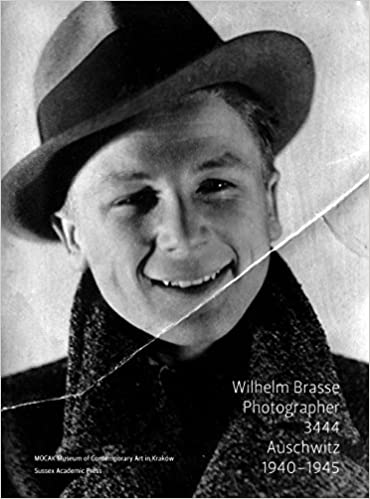

Wilhelm Brasse (1917−2012) came from an Austrian-Polish family whose aunt was a professional photographer in Katowice, Poland. He studied under his aunt and followed in her footsteps. However, after the Nazis invaded Poland in 1939, Brasse was taken to the local headquarters of the Schutzstaffel (SS) for interrogation. He refused to swear allegiance to Hitler and the Nazis as well as refusing to enlist in the Wehrmacht. Brasse was imprisoned for three months and after being released, he attempted to escape from Poland to join the exiled Polish military in London. Unfortunately, Brasse was captured and immediately deported to KZ Auschwitz in August 1940. His arm was tattooed with prisoner no. 3444 and upon learning of Brasse’s technical skills (including his ability to speak German), Höss gave him a choice: assignment to the camp’s Erkennungsdienst unit or death.

The Erkennungsdienst

The Erkennungsdienst, or Police Records Department was established in January 1941 at Auschwitz I (main camp; construction of the extermination camp, Auschwitz II-Birkenau, did not begin until October 1941). An alcoholic gambler, SS-Hauptscharführer (i.e., master sergeant) Bernhard Walter (1911−1979) transferred from KZ Sachsenhausen to run the Auschwitz Erkennungsdienst. His deputy was SS-Rottenführer Hans Hoffmann (b. 1919−?). These two SS soldiers commanded a group of ten photographers including Brasse as well as darkroom technicians, retouchers, and designers.

In September 1941, six hundred Soviet POWs and 250 Polish prisoners became the first victims of the Zyklon B poison cannisters. Shortly afterward, more Soviet POWs were rounded up in the execution yard outside Block 11. There, they were axed to death by the SS guards. Walter made a film of the men dying and showed it to the men of the Erkennungsdienst. Brasse recalled the sadistic pleasure Walter displayed during the “show.” This carried over to Walter’s enthusiasm of taking photos of the dead and suffering. Walter and Hoffmann personally took pictures of prisoners after being shot while trying to escape, those who hanged themselves, or threw themselves into the electrified fence.

The Photographs

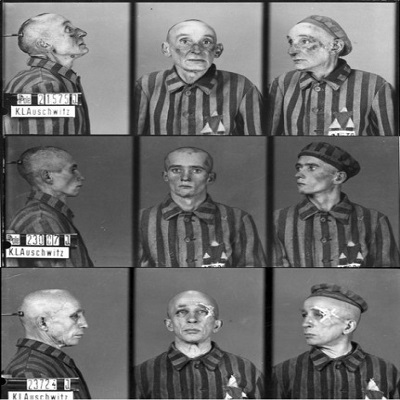

The original purpose of the Erkennngsdienst was to record “identity photographs” of the inmates. These were essentially mug shots with three views: the front and from each side. Each prisoner was required to have their faces shaved and their prison shirts legibly embroidered with their respective numbers and colored triangles identifying the prisoner’s status. Headwear was required for both men (caps) and women (shawls). When summoned, the inmates queued up in front of Block 26 in order of their numbers from low to high. Anyone in line⏤man, woman or child⏤who “misbehaved” was savagely beaten by the SS guards.

Between the first quarter of 1941 and the evacuation of the camp four years later, it is estimated that a total of 200,000 photographs were taken. Arriving deportees selected for immediate death were not photographed, tattooed, or registered.

Eventually, the work of Brasse’s unit included taking photos of camp events, medical experiments, and clandestine images of the sorting ramp at Auschwitz-Birkenau (it is believed that many of the photos capturing the sorting process were taken by either Walter or Hoffmann).

Beginning in January 1942, the notorious camp doctors (e.g., Josef Mengele) began to arrive at Auschwitz. Mengele found Brasse’s photographs and liked them enough to have Brasse photograph the victims of the medical experiments, including twins and people with congenital disorders.

Czesława Kwoka

Czesława Kwoka (1928−1943) was a Polish Catholic girl imprisoned by the Nazis in Auschwitz. Her crime? She was Polish. Her “identity photograph” was taken by Wilhelm Brasse. She and her mother were arrested and deported on 13 December 1942. Although both were spared immediate death upon arrival, Czesława’s mother (no. 26946) died two months later. Czesława (no. 26947) followed her mother in death one month later on 12 March 1943.

Between 1940 and 1945, about 230,000 children (aged eighteen or less) were deported to Auschwitz. This represented almost 18% of the total number of people (1.3 million) deported to the extermination camp. The majority of the children were Jewish (about 216,000). Only 20,000 children were registered (as I mentioned earlier, persons immediately selected for the gas chamber were never recorded at the camps). No more than 650 of the deported children survived.

Brasse remembered taking Czesława’s photograph. He described that experience to a BBC correspondent:

“She was so young and so terrified. The girl didn’t understand why she was there and she couldn’t understand what was being said to her.

“So this woman Kapo (a prisoner overseer) took a stick and beat her about the face. This German woman was just taking out her anger on the girl. Such a beautiful young girl, so innocent. She cried but she could do nothing.

“Before the photograph was taken, the girl dried her tears and the blood from the cut on her lip. To tell you the truth, I felt as if I was being hit myself but I couldn’t interfere. It would have been fatal for me. You could never say anything.”

Preservation of the Photographs

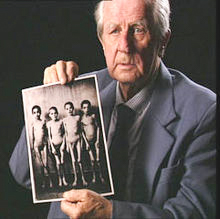

During the evacuation of the camp in January 1945, Brasse and Bronisław Jureczek were ordered to destroy the photographs while Walter supervised. Brasse decided to try and save as many photos as possible. While Walter was observing, Brasse would stuff the photos in the furnace with wet photo paper. He ensured the volume of paper was enough to prevent the smoke from escaping and the fire would go out. After Walter left the building, Brasse and Jureczek retrieved the surviving photos from the furnace. They were able to hide the photos and just before evacuating the camp, the two men boarded up the door to the laboratory to prevent anyone from gaining access to the collection of photos. It is remarkable that the men were able to save 38,916 photos (31,969 men and 6,947 women).

After liberation, the photographs and negatives began a journey that led to the Polish Red Cross and finally, to the State Museum in Oświęcim (the town nearest to Auschwitz)⏤today, it is the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum. A former Auschwitz prisoner, Karol Rydecki (no. 3011), was put in charge of cataloguing the photos. The photographs reside in the museum’s archives as part of the “Protection of the Documentation of KL Auschwitz.” Yad Vashem is the other repository of camp photographs.

Liberation and Post-War

Brasse was moved to a KZ Mauthausen subcamp in early 1945 as the Soviet army advanced through Poland. He was liberated by the Americans in early May 1945. Walter was captured and served three years in a Polish prison before returning to Germany and a job (ironically) as a movie projectionist in Bavaria. Hoffmann disappeared and was never heard from again.

Returning to his hometown of Żywiec (twelve miles from Auschwitz), Brasse tried taking up portrait photography again but he was haunted by his years in Auschwitz.

For the rest of his life, Wilhelm Brasse never again took a photo.

✭ ✭ ★ Learn More About The Auschwitz Portraitist ✭ ★ ★

Brasse, Wilhelm. Wilhelm Brasse: Photographer. 3444. Auschwitz. 1940−1945. East Sussex: Sussex Academic Press, 2012.

Campbell, Ali. Photography Ethics in Auschwitz: The Story of Wilhelm Brasse. 2016-2017 Gideon Klein Scholar. www.cssh.northeastern.edu

Dobrowolska, Anna (producer) and Irek Dobrowolski (director). The Portraitist. Rekontrplan Film Group, 2005. A 52-minute Polish documentary about the life and work of Wilhelm Brasse.

Disclaimer:

There may be a chance that after we publish this particular blog, the video links associated with the blog are no longer accessible. We have no control over this. Many times, whoever posts the video has done so without the consent of the video’s owner. In some cases, it is likely that the content is deemed unsuitable by YouTube. We apologize if you have tried to access the link and you don’t get the expected results.

What’s New With Sandy and Stew?

Sandy and I would like to wish all of you Happy Holidays. We hope you all stay safe and enjoy your holidays. Like most of you, we are looking forward to seeing the New Year ushered in and hopefully, experience a return to “normality”⏤whatever that might be.

Thank you to all of you who subscribe to our bi-weekly blogs. It seems there isn’t a day that goes by where we don’t increase our readership. Please let your history buff friends and family members know about our blogs.

Someone Is Commenting On Our Blogs

I’d like to thank Wendy W-P for introducing me to Loraine R. I read an article written by Wendy about her trip to Paris with Loraine, her cousin. It turns out that one of their stops was to see Loraine’s father, Phillip (Pete) Jackson. Many of you may recognize her father. He was the son of Dr. Sumner and Toquette Jackson. The Jackson family was involved with the French Resistance and their story is very interesting (Alex Kershaw: Avenue of Spies). One of the stops in my new book, Where Did They Put the Gestapo Headquarters? is the former apartment where the Jacksons lived on Avenue Foch. Loraine has graciously offered to share some of the family images for the new book. I look forward to hearing some of her stories that I hope we can turn into a blog.

If there is a topic you’d like to see a blog written about, please don’t hesitate to contact me. I love hearing from you so keep those comments coming.

Why Would You Want to Buy Our Walking Through History Books?

Simple.

You like to travel and experience history and historical events. You like to see original buildings that had a significant impact on the people and events of the history you’re engaged with. You want to know the stories behind the brick and mortar in front of you.

The walking tour books are meticulously researched so you can go directly to those sites and learn about the building’s history as well as an introduction to some of the more interesting people associated with it.

We Need Your Help

Please tell your friends about our blog site and encourage them to visit and subscribe. Sandy and I are trying to increase our audience and we need your help through your friends and social media followers.

Thank You

Sandy and I appreciate you visiting with us. We have some exciting things on the horizon, and we’ll keep you updated as we go along.

Share This:

Follow Stew:

Find Stew’s books on Amazon and iBooks.

Please note that we do not and will not take compensation from individuals or companies mentioned or promoted in the blogs.

Walks Through History

Walks Through History

Copyright ©2020 Stew Ross

An English subtitled DVD of the story of Wilhelm Brasse and his photos is available at reasonable cost from http://auschwitz.org/en/type-of-publication/multimedia/the-portraitist,173.html#2

I just viewed it.

Thanks Mel for the DVD reference. I plan on taking a look at it. STEW